The Korowai Tribe: Inside the Last Known Cannibal Society of Papua

Introduction

Hidden deep within the dense rainforests of southeastern Papua, Indonesia, the Korowai tribe has long fascinated anthropologists, travelers, and curious minds around the world. They are often labeled as one of the last known practicing cannibal societies, a label that has sparked intrigue and controversy alike. Living in towering treehouses, high above the forest floor, the Korowai have remained relatively isolated from the modern world until only a few decades ago.

But beyond the sensationalized headlines of cannibalism, lies a rich culture that has evolved in harmony with the harsh but bountiful tropical landscape. The Korowai people possess a deeply rooted spiritual belief system, an intricate social structure, and a way of life that offers invaluable insights into human adaptation and survival.

This article aims to provide an in-depth exploration of the Korowai tribe, delving into their history, culture, and beliefs. We will also examine the controversial topic of cannibalism, separating fact from fiction, and discuss the impact of modern exposure on this remarkable indigenous society. Whether you’re an anthropologist, a traveler, or someone with a deep interest in human cultures, this comprehensive guide will reveal the truth behind the myths and offer a nuanced understanding of the Korowai tribe of Papua.

Who Are the Korowai?

The Korowai, also known as the Kolufo, are an indigenous tribe living in the southeastern part of Papua, Indonesia. Their population is estimated to be around 3,000 to 4,000 individuals, spread across the lowland rainforests near the Eilanden and Becking Rivers. The Korowai region is remote and can only be accessed by small aircraft or multi-day treks through dense jungle.

The Korowai people speak the Korowai language, which belongs to the Trans-New Guinea language family. It is a complex and expressive language, reflective of the tribe’s intimate connection to their environment. Each clan has its own dialect and traditions, but they all share a common cultural foundation based on animism, self-sufficiency, and communal living.

Compared to other Papuan tribes, the Korowai have been among the least influenced by outside contact until relatively recently. While many neighboring groups converted to Christianity or Islam during the 20th century, the Korowai remained largely untouched by missionaries, colonial powers, or trade networks until the 1970s.

Today, the Korowai are often caught between two worlds: the ancient customs of their ancestors and the rapid changes brought about by tourism, government intervention, and globalization. Despite this, many Korowai still practice traditional ways of living, including hunting, foraging, and building homes high in the treetops.

History of Discovery

The Korowai tribe remained completely isolated from the outside world until the late 20th century. It wasn’t until 1974 that Dutch missionaries and anthropologists made the first known contact with the tribe. Before this encounter, the Korowai were unaware of the existence of people beyond their forested homeland, and the outside world had never documented their unique way of life.

This first contact sparked significant interest from researchers and anthropologists who were eager to learn about the tribe’s customs, social structures, and survival strategies. The Korowai’s treetop dwellings, complex spiritual beliefs, and reports of ritualistic cannibalism attracted worldwide attention. Anthropologists such as Peter van Arsdale and journalists like Paul Raffaele played a major role in introducing the Korowai to the global audience.

Over the next few decades, numerous expeditions ventured into the Korowai territories, often accompanied by film crews and reporters. Documentary series from networks like National Geographic and Discovery Channel portrayed the Korowai as one of the last uncontacted tribes practicing cannibalism. While some of these portrayals were accurate, others were dramatized to cater to sensationalist media demands.

These early interactions were not without challenges. Language barriers, cultural misunderstandings, and differing worldviews created tension and distrust. However, many Korowai clans were eventually receptive to outsiders, particularly when offered tools, medicine, and clothing.

Despite their increasing visibility, large portions of the Korowai territory remain unexplored and inaccessible. Many clans continue to live traditionally and avoid outside contact. Even today, researchers believe that some Korowai families have never seen a Westerner and still view the jungle as the center of the universe.

Culture and Daily Life

Daily life for the Korowai is deeply tied to their forest environment. They are semi-nomadic and rely on hunting, fishing, and foraging for their subsistence. Men typically hunt wild pigs, cassowaries, and other small forest animals using bows and arrows, while women gather sago, bananas, and tubers and are responsible for cooking and raising children.

Perhaps the most iconic feature of Korowai culture is their remarkable architecture: treehouses built as high as 30 meters above the ground. These homes serve both practical and symbolic purposes. Elevated structures help avoid flooding, offer protection from insects and animals, and symbolically distance the inhabitants from malevolent spirits believed to roam the forest floor.

Korowai treehouses are built entirely from natural materials—wooden beams, vines, and palm leaves—without the use of metal tools. Construction is a communal effort involving both men and women, and it often takes several days to complete a single home. The height and complexity of a treehouse can signify a family’s status or spiritual purity within the clan.

Clothing is minimal and primarily functional. Men traditionally wear penis sheaths (koteka), while women wear grass skirts made from sago leaves. Body paint, feathers, and bone jewelry are used during ceremonies or as personal decoration. Tattoos are uncommon, but scarification may be practiced as a rite of passage.

Community life revolves around cooperation and kinship. Clans are patrilineal, and disputes are often settled through negotiations rather than violence. Storytelling, oral traditions, and singing play an important role in preserving historical memory and cultural values.

The Korowai also maintain extensive knowledge of medicinal plants and natural remedies. Shamans and elders treat ailments using herbs, rituals, and spiritual guidance. This deep ecological knowledge is a cornerstone of their survival and a testament to their harmonious relationship with nature.

Korowai Belief Systems and Rituals

The spiritual world of the Korowai tribe is rooted in animism — the belief that all living things and natural objects possess a spirit. This belief governs every aspect of their lives, from daily decisions to major communal rituals. The Korowai see the forest not merely as a resource but as a realm filled with both protective and vengeful spirits that must be appeased through rituals and careful behavior.

One of the most important figures in Korowai society is the shaman, known locally as a “guru.” These spiritual leaders are considered intermediaries between the human world and the spirit realm. Gurus diagnose illnesses, conduct healing ceremonies, and interpret signs from the forest spirits. Healing often involves the use of sacred chants, ritual dances, and herbal remedies derived from the jungle.

Rituals mark significant stages in the Korowai life cycle, such as birth, initiation into adulthood, marriage, and death. Initiation rituals for boys often include endurance tests and seclusion in the forest, while girls may be taught sacred songs and domestic skills by older women. These rites reinforce tribal identity and cultural continuity.

Death is a highly spiritual event in Korowai culture. The tribe believes that the soul of the deceased journeys to the land of the ancestors, but it can only do so peacefully if proper burial rituals are observed. Corpses are typically buried near the family home, though in some cases cremation or treetop platforms are used to allow the soul to ascend more easily.

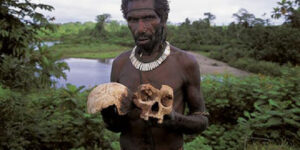

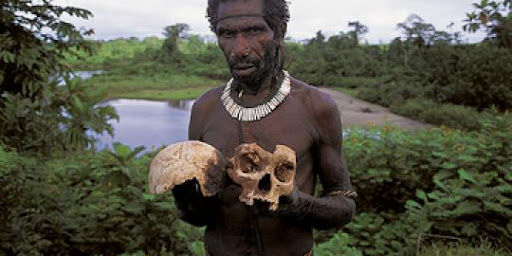

A particularly feared element of Korowai belief is the concept of the “khakhua”—a witch or malevolent spirit disguised as a human. Khakhua are blamed for sudden deaths or unexplained misfortunes, and if someone is suspected of being one, they may be executed by the community in an act that has historically been linked to ritual cannibalism. These executions are not merely punishments but are believed to restore cosmic balance and protect the tribe from further harm.

Despite increasing contact with outsiders and exposure to new belief systems, many Korowai still maintain their traditional cosmology. Their rituals and spiritual practices continue to shape their identity and define their place within both the natural and supernatural world.

Cannibalism: Myth vs Reality

The association of the Korowai tribe with cannibalism has long captured the public’s imagination. While sensational media coverage often portrays the Korowai as active cannibals, the truth is far more complex and rooted in cultural, spiritual, and social contexts. It is crucial to distinguish between the mythologized accounts and the documented anthropological findings.

Historically, reports suggest that acts of cannibalism among the Korowai were not practiced for sustenance but were rather part of a justice-based belief system. These acts were typically linked to the execution of individuals believed to be khakhua—witches who were said to bring death and misfortune to the community. Consuming the flesh of a khakhua was viewed as a way to neutralize evil, avenge lost lives, and restore harmony within the tribe.

Anthropologists and journalists who visited the region in the 1980s and 1990s, such as Paul Raffaele and Peter van Arsdale, documented testimonies from Korowai members who openly discussed past practices of ritualistic cannibalism. However, many of these accounts could not be independently verified and were often complicated by translation barriers and the possibility of performative responses aimed at impressing outsiders.

It is important to note that not all Korowai clans practiced cannibalism, and those who did appear to have done so rarely and under specific spiritual circumstances. Moreover, with increased exposure to external influences—particularly Christian missionaries, government programs, and tourism—such practices have drastically diminished or ceased entirely.

Today, many Korowai individuals vehemently deny current involvement in cannibalistic rituals and express discomfort with how these narratives define their identity. Some have even accused journalists and filmmakers of exaggerating or fabricating stories to boost viewership, casting doubt on the accuracy of some high-profile documentaries.

While cannibalism may have been a historical aspect of some Korowai groups, it should not overshadow the rich complexity of their culture. Focusing solely on this element not only distorts public perception but also risks dehumanizing a people whose traditions, resilience, and spiritual depth deserve far more balanced understanding.

Interaction with the Outside World

Since their first documented contact in the 1970s, the Korowai people have gradually been introduced to outsiders through the efforts of missionaries, government programs, researchers, and the growing tourism industry. These encounters have created a dynamic and sometimes controversial intersection between traditional lifestyles and modern influences.

Christian missionaries were among the first to attempt long-term settlement in Korowai territory. Their goal was to convert the Korowai to Christianity and encourage them to abandon what were seen as primitive customs. While some tribespeople have embraced Christian teachings, others have resisted, fearing the loss of ancestral traditions and spiritual balance.

Government programs have also played a role in resettling some Korowai into designated villages, offering access to education, healthcare, and basic infrastructure. While this has improved living standards for some, it has also led to a decline in traditional practices, languages, and skills. Many younger Korowai now grow up with limited exposure to their heritage as they attend state schools or seek work in nearby towns.

Tourism has been both a blessing and a curse for the Korowai. On one hand, it brings economic opportunities, such as guiding services, the sale of handicrafts, and village hosting. On the other, it can lead to exploitation, cultural staging, and the commodification of sacred rituals. Some documentaries and photojournalistic reports have been criticized for staging events or pressuring tribespeople to reenact cannibalistic scenes for shock value.

The Korowai have had mixed reactions to outsiders. Some view them as allies or providers of tools and medicines, while others see them as a threat to traditional values. Trust is often earned slowly and must be maintained through respect and reciprocity.

In recent years, there has been growing awareness among anthropologists and ethical travelers about the importance of consent, representation, and preserving cultural dignity. Initiatives now encourage more collaborative research and tourism practices that benefit local communities and safeguard their autonomy.

As the Korowai continue to engage with the wider world, they stand at a crossroads—balancing the preservation of their unique identity with the pressures and promises of modernization. Their choices in the coming decades will shape not only their future but also the global understanding of indigenous resilience and adaptation.

Modern Changes and Cultural Erosion

The Korowai tribe today is experiencing a profound cultural shift. As government policies, religious missions, and globalization reach further into remote areas of Papua, traditional Korowai ways of life are slowly eroding. This transformation is most visible among the younger generation, many of whom are choosing to abandon traditional practices in favor of modern conveniences and education.

One of the most impactful changes has been the relocation of Korowai families to government-sponsored villages. While these settlements offer access to schools, health clinics, and markets, they also draw people away from their ancestral lands. As a result, ancient skills such as hunting with traditional tools, building treehouses, and performing sacred rituals are being lost at an alarming rate.

The influence of organized religion, particularly Christianity, has also played a significant role in reshaping Korowai culture. While it has brought certain benefits—such as community support networks and moral teachings—it has often conflicted with traditional beliefs. Some rituals, including animistic ceremonies and spirit invocations, have been discouraged or labeled as taboo.

Globalization, including the spread of smartphones and satellite technology, is introducing the Korowai to global media, politics, and consumer culture. Some tribal members now wear Western clothing, use solar-powered gadgets, and even access online platforms via mobile networks in nearby towns. While this offers new opportunities, it also accelerates the decline of indigenous languages and cultural identity.

Despite these pressures, efforts are underway to preserve Korowai traditions. NGOs and anthropologists are working with village elders to document oral histories, language, and spiritual knowledge. Cultural education programs for children aim to instill pride in their heritage, ensuring that traditional knowledge is passed down even in a changing world.

The future of the Korowai depends on a careful balance between embracing beneficial aspects of modernity and maintaining the essence of their unique cultural heritage. Without deliberate preservation efforts, there is a real risk that the world could lose one of its most fascinating and resilient indigenous cultures.

Representation in Media and Ethical Considerations

The Korowai tribe has garnered widespread attention in international media, often portrayed through the lens of exoticism and sensationalism. Documentaries, news articles, and photo essays have frequently focused on the more extreme aspects of Korowai culture—particularly cannibalism and treehouse living—creating a narrative that is both fascinating and deeply problematic.

While such coverage can raise awareness about the existence of remote indigenous groups, it often does so at the expense of accuracy and dignity. Many reports rely on outdated or unverified information, and in some cases, media crews have been accused of staging scenes or pressuring locals to reenact traditional practices purely for entertainment. This exploitation not only distorts public understanding but can also harm the community itself by reinforcing stereotypes and undermining cultural integrity.

Ethical concerns have been raised by anthropologists, journalists, and advocacy groups about how the Korowai are represented. Key issues include informed consent, cultural misrepresentation, and lack of benefit-sharing. Often, the subjects of these reports receive little or no compensation, and their stories are told through an outsider’s perspective, stripping them of agency and nuance.

Some modern media creators and researchers are attempting to change this narrative by adopting more collaborative and respectful methods of documentation. Participatory media projects, for instance, involve Korowai individuals in the storytelling process, ensuring that their voices are heard and their perspectives accurately represented. These efforts promote cultural empathy, encourage mutual learning, and pave the way for more ethical cross-cultural engagement.

There is also a growing call for policy frameworks that regulate indigenous media representation. These would include guidelines for obtaining permission, respecting local customs, and ensuring that communities benefit from the exposure. Institutions such as UNESCO and indigenous rights organizations are working to support these initiatives.

Ultimately, the global audience bears responsibility for how it consumes stories about the Korowai and similar communities. Seeking out balanced, respectful, and well-researched content—and questioning sensational portrayals—can contribute to a more just and informed understanding of one of the world’s most unique cultures.

The Future of the Korowai People

As the Korowai tribe stands on the brink of transformation, their future depends on a combination of cultural resilience, ethical engagement, and sustainable development. Preserving their unique identity while embracing elements of the modern world is a complex challenge—one that requires cooperation among the Korowai, governments, NGOs, researchers, and the global community.

Central to the tribe’s future is education that respects traditional knowledge while offering new opportunities. Culturally relevant curricula, taught in both native dialects and national languages, can empower the younger generation to participate in modern society without losing touch with their roots.

Economic sustainability is another pillar of long-term success. Initiatives like eco-tourism, fair-trade handicrafts, and community-owned businesses can provide income while protecting cultural and environmental resources. However, these must be guided by ethical principles to avoid exploitation or dependency.

Healthcare and infrastructure should also be improved with the input of local communities. Solutions tailored to the needs and values of the Korowai are more likely to succeed than top-down programs. Mobile clinics, telemedicine, and training local health workers are promising models that balance innovation with respect for autonomy.

Preserving the Korowai’s ancestral lands is perhaps the most urgent task. Deforestation, mining, and illegal logging threaten the ecological foundation of their lifestyle. Land rights legislation and conservation partnerships are vital to securing their territory and maintaining environmental balance.

Most importantly, the Korowai must be central participants in shaping their own future. This means honoring their voices, protecting their rights, and supporting their self-determination. Only through genuine partnership and mutual respect can the world ensure that this extraordinary culture not only survives but thrives in the generations to come.