History of Freeport Gold Mine in Papua, Indonesia

The Freeport gold mine in Papua, formally known as the Grasberg Mine, is one of the largest gold and copper mines in the world. Operated by PT Freeport Indonesia, a subsidiary of Freeport-McMoRan based in the United States, the mine has been at the center of economic development, environmental debates, and indigenous rights issues in Indonesia.

This article provides a thorough historical overview of Freeport’s operations in Papua—from the original discovery of mineral-rich ore to its global economic impact and the complex geopolitical issues that surround it.

1. The Geographic and Geological Setting

1.1 Where is the Grasberg Mine?

The Grasberg Mine is located in the remote highlands of Papua Province, in the Mimika Regency, near the town of Timika. Nestled in the Sudirman Mountains, it sits at an altitude of over 4,000 meters (13,000 feet), making it one of the highest-altitude mines in the world.

1.2 What Makes It Special?

The Grasberg deposit is rich not only in gold but also in copper and silver. It is among the top five largest gold deposits and second-largest copper deposits on the planet.

2. The Discovery of the Gold Deposit

2.1 The First Exploration: Jean Jacques Dozy

In 1936, Dutch geologist Jean Jacques Dozy discovered a mysterious outcropping of ore he named “Ertsberg” (Ore Mountain) while exploring the rugged terrain of Dutch New Guinea. However, World War II and logistical challenges delayed follow-up investigations for decades.

2.2 Re-exploration and Confirmation

In the 1950s and 1960s, further exploration resumed when the Indonesian government allowed foreign investments. In 1967, Freeport Sulphur Company (later Freeport-McMoRan) signed the first Contract of Work (CoW) with the Indonesian government, becoming the first foreign company to secure such a deal under the Suharto regime.

3. Establishment of Freeport Indonesia (PT FI)

3.1 Formation of PT Freeport Indonesia

In 1967, PT Freeport Indonesia was established as the local subsidiary of Freeport-McMoRan to operate the Ertsberg mine. The company brought advanced technology and substantial investment, and by 1973, Ertsberg was in full operation.

3.2 Ertsberg’s Rapid Depletion

Although Ertsberg proved fruitful, its ore reserves were quickly depleted. This accelerated Freeport’s exploration of nearby areas, which led to the discovery of the Grasberg deposit in 1988.

4. The Rise of Grasberg: A Mining Giant

4.1 Discovery of Grasberg

Grasberg turned out to be much larger and richer than Ertsberg. Mining operations quickly shifted focus, and by the 1990s, Grasberg had become the centerpiece of Freeport’s global operations.

4.2 Expansion and Modernization

To access Grasberg’s massive ore body, Freeport invested billions in infrastructure:

- Roads, airports, and living quarters in the otherwise inaccessible highlands.

- A 100km slurry pipeline to transport concentrate to the port at Amamapare.

- Underground mining systems to extend the mine’s life.

5. Ownership and Partnerships

5.1 Initial Ownership

Originally, Freeport held a 90% stake in the project, while the Indonesian government held the remaining 10%.

5.2 Involvement of Rio Tinto

In 1996, Rio Tinto, a global mining giant, acquired a stake in Freeport’s future production, particularly from Grasberg’s expansion plans.

5.3 Divestment and Indonesian Majority Control

In 2018, following years of political pressure, Freeport agreed to divest a majority of its stake. PT Inalum (now MIND ID), a state-owned Indonesian holding company, acquired a 51.2% stake, effectively giving the Indonesian government majority control.

6. Socioeconomic Impact in Papua

6.1 Employment and Infrastructure

Freeport is the largest private employer in Papua. It has:

- Created over 30,000 direct and indirect jobs

- Built infrastructure including roads, schools, and hospitals

- Contributed significantly to local GDP

6.2 Economic Contributions

Freeport contributes billions of dollars annually through taxes, royalties, dividends, and export earnings. As of 2020, the mine had generated over $100 billion in revenue since inception.

7. Environmental Controversies

7.1 Waste Disposal Practices

One of the most controversial aspects of Freeport’s operations is its riverine tailings disposal system. Environmentalists argue that it causes:

- River pollution

- Habitat destruction

- Deforestation and biodiversity loss

7.2 Glacial Melting and Climate Impact

Mining at such high altitudes has also been linked to glacial melting in the region, with potential climate implications.

8. Indigenous Rights and Human Rights Issues

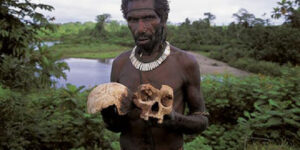

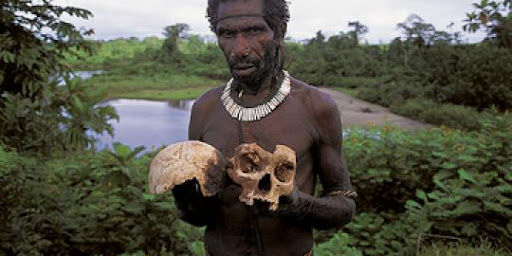

8.1 Indigenous Papuan Communities

The Amungme and Kamoro tribes consider the mining area sacred. The expansion of mining activities has led to:

- Loss of traditional land

- Social dislocation

- Cultural erosion

8.2 Allegations of Abuse

There have been persistent allegations of:

- Human rights violations by security forces protecting the mine

- Lack of adequate compensation to affected communities

9. Security and Militarization

Due to separatist tensions in Papua, Freeport has historically relied on Indonesian military and police forces for protection, often funded by the company.

9.1 Armed Conflicts

There have been multiple attacks on the mine and its workers by separatist groups, including the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB-OPM).

10. The 2018 Transition Agreement

10.1 Road to Divestment

In a landmark deal in 2018, Freeport agreed to:

- Divest majority ownership to Indonesia

- Convert its Contract of Work into a Special Mining Permit (IUPK)

- Continue operations until 2041 under new terms

10.2 Indonesia’s Strategic Victory

This move was celebrated as a nationalist victory, allowing Indonesia greater control over its natural resources.

11. Modernization and the Shift Underground

With the depletion of the open-pit mine, Freeport has transitioned to underground operations:

- Deep Mill Level Zone (DMLZ)

- Grasberg Block Cave (GBC)

These underground mines are now among the largest globally in terms of output.

12. Economic and Strategic Importance Today

12.1 Global Significance

The Grasberg Mine continues to rank among the top gold and copper producers in the world.

- 2023 output: Over 1.5 million ounces of gold and 1.2 billion pounds of copper

- A key supplier for global electronics and green energy industries

12.2 National Pride and Economic Engine

For Indonesia, the mine remains a strategic asset:

- Vital for state revenues

- Showcases successful resource nationalism

- Central to the country’s industrial policy and development agenda

13. Challenges and the Future of Freeport Papua

13.1 Environmental Rehabilitation

There are increasing calls for Freeport to:

- Invest in long-term environmental restoration

- Reduce emissions and pollution

- Comply with global sustainability standards

13.2 Social License to Operate

Ongoing tensions with local communities and human rights groups mean Freeport must:

- Improve local engagement

- Share more benefits with Papuans

- Promote inclusive development

13.3 Geopolitical Risk

With continued independence movements in Papua, the mine’s future remains politically sensitive.

Conclusion

The history of Freeport’s gold mine in Papua is a microcosm of the complex intersection between resource extraction, geopolitics, indigenous rights, environmental sustainability, and national sovereignty. While it has brought immense wealth and modernization, it has also raised serious concerns around justice, fairness, and long-term impact.

As Indonesia takes on a more assertive role in managing its natural resources, the Freeport story serves both as a warning and a guide for sustainable mining practices in the 21st century.